A perspective on sustainable governance and Swacchh Bharat Mission

The sanitation problem in India cannot be understated. While decades of sustained economic growth have made India the seventh-largest economy in the world today, the provision of public services such as water, sanitation, solid waste management, and drainage continue to be a challenge. A lot of programmes have been started in the past decades, but none of them could fully tackle the water management and sanitation in a holistic and effective manner. With an urgent need to re-energise and remodel its approach, the Government of India launched the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) in 2014. Also the Sustainable Development Goal 6 “represents a significant deepening of ambition, aiming to ‘achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation’ by 2030”[1]. Today, India has a historic opportunity to address the problem of sanitation in its entirety using the momentum generated by SBM to realise the ambition of sustainable sanitation, one of the prime goals of SDGs.

SBM brought sanitation and water “on the table”. Increasingly projects and NGO are settling for improving sanitation. Campaigns and events like Global Citizen point citizens to realize the urge for a Swachh Bharat. GOI creates various policies in and around the WASH umbrella, not only toilet building activities but also integration of sectors like menstrual hygiene management (MHM Guidelines), corporate social responsibility (Swachh Kosh) or WASH in school activities (Swachh Vidyalaya).

Though there is no shortage of policy level recommendations at the central level, their impact and infiltration at the ground level is very limited. To create sustainability, these policies need to work together with the implementation of its programs. There is dire need for thought leadership to move this forward. Policy advocacy is not merely the creation of laws and regulations; it must create an enabling environment for sustainable change. Sanitation also needs good governance. UNESCO understands Governance as an act.

“… to refer to structures and processes that are designed to ensure accountability, transparency, responsiveness, rule of law, stability, equity and inclusiveness, empowerment, and broad-based participation. Governance also represents the norms, values and rules of the game through which public affairs are managed in a manner that is transparent, participatory, inclusive and responsive. Governance therefore can be subtle and may not be easily observable. In a broad sense, governance is about the culture and institutional environment in which citizens and stakeholders interact among themselves and participate in public affairs. It is more than the organs of the government.”[2]

The need is to reach these solutions to the last mile with an efficient governance and effective implementation. The right governance system and a model to help address “Produce to Use” strategy is important. This process is indeed not an easy one, but efforts and motivation are the first step towards achieving a “Swachh Bharat”. However, a “one size fits all” didn´t, does and will not work in the Indian context. To tackle the problem of the last mile, a closer look in the Governance body and process must be taken forward. Some important areas that should be addressed are explained here.

Integration of the full water and sanitation cycle

The image of sanitation should move beyond “going to the toilet”. Since SBM started in 2014, the focus from governance has been construction of toilets. With the current mission, India runs the risk of neglecting the whole wastewater cycle. Sanitation is a complex topic that has significant impact on health, nutrition, security, environment and human rights. Per the World Bank 47% of children could be saved from diarrhoea if sanitation systems would be offered broadly.[3]

Understanding sanitation often does not include the big picture of sanitation. Once a toilet is constructed, it should be maintained, the disposal of human waste has to be safely managed and people actually have to use the toilet regularly. On top of that, sanitation also includes the knowledge of hygiene such as handwashing activities and menstrual hygiene actions. Sewage systems, on-site systems like septic tanks and other solutions need prioritization. The conjunction from sanitation to drinking water is not applicable. SBM has set numbered goals in toilet construction and ODF, which are handy to monitor. But it lacks the full understanding and implementation of policies that focus on the full cycle. “This implies paying attention not only to wastewater conveyance and treatment, but also to less visible concerns like poor construction of on-site systems and lack of operations and maintenance”[4]. The Shit Flow Diagram (SFD) tool is a good visualization for explaining the whole cycle. This leads to the question of how sustainable the current governance/policy of SBM is.

Sustainable Governance and long term vision

SBM with the deadline of 2019 tries to become ODF. But what comes after that deadline? What if all the toilets constructed now will not be in use any more? The need for sustainable solutions should be taken seriously, not only on the environmental perspective but also for economic reasons and financing of sanitation project. Per the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA), and the members of the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council as the “Bellagio Principles for Sustainable Sanitation” during its 5th Global Forum in November 2000: Human dignity, quality of life and environmental security at household level should be at the centre of any sanitation approach.

- In line with good governance principles, decision making should involve participation of all stakeholders, especially the consumers and providers of services.

- Waste should be considered a resource, and its management should be holistic and form part of integrated water resources, nutrient flow and waste management processes.

- The domain in which environmental sanitation problems are resolved should be kept to the minimum practicable size (household, neighbourhood, community, town, district, catchments, city)[5]

Sustainability in sanitation the following points should be implemented for sustainable sanitation: Waste should be considered a resource, and its management should be holistic and form part of integrated water resources, nutrient flow and waste management processes. A long-term vision on sanitation and drinking water after 2019 should be published.

Capacity building and effective governance

The capacity and resources for sanitation are limited. Especially in urban areas, regulations need to be implemented for proper waste disposal. A “one size fits all” approach is not working.[6] Communication between local bodies and higher institutions is missing. Local communities don’t often communicate their needs to the political level. Effective governance means to create rules and norms which fit local realities. This means also a democratic, inclusive approach, where voices of the beneficiaries are considered. The legislative framework shifts the major responsibility of sanitation and wastewater management to state and/or local bodies. National agendas on sanitation influence the various state sanitation agendas. Especially financial support mainly comes from national ministries. On the national level, the Ministry for Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) mainly leads the SBM for rural areas, whereas the Ministry for Urban Development (MoUD) established an urban SBM. WASH activities like Swachh Vidyalaya are coordinated by the Ministry of Human Resource Development. If it comes to sanitation systems and local infrastructure within households, the Ministry for Housing and Urban Poverty Allevation (HUPA) takes the lead. The capacity for sanitation issues in government bodies has been implemented, but effectiveness in communication and achieving goals still is equivocal. That gives the feeling of rather impulsive actions in WASH that lack management of implementation actions, especially in local areas.

Ownership and Collaboration

Everybody does it but less people care for it. Sanitation systems tend to create the impression that you can flush and give away human waste. “Your own business” no longer is your own business when it comes to sanitation. It needs the individual to understand the scope of WASH impacts every single person has. Creating policies on national level is simply not enough to reach Swachh Bharat. “Given the scale of the challenge and India’s very disparate socio-political landscape, performance varies from State to State and even within a State. Too often we depend on an individual without making the change systemic”, Naina Lal Kidwai stated in an online discussion.[7]

Governance has to go beyond creating rules and policies towards integrating a nations citizen. That requires a sense of responsibility and taking on ownership for their own good. “The positive incentives identified for prioritisation of sanitation are necessary, but not sufficient. Peoples’ perceptions about autonomy and authority shape how they respond to incentives to prioritise sanitation”.[8] Activities on behaviour change are therefore very much needed. Creating solutions by collaboration and leveraging each other’s strength is the way forward.

In the first year of SBM, more than 5.8 million toilets were constructed in rural areas and about 1 million in urban spaces.[9] How many of them are in use? Are they maintained well? Is the waste disposed safely? Who disposed waste? All these and many more questions come up. The problem is that people expect GOI or state governments to subsidize toilet constructions, conduct workshops or set up septic tanks, but they do not plan to engage themselves. Sanitation at this level is not simply a public service. It’s a goal everybody should work on. “The successes we are seeing now are largely due to the leadership and commitment of district officials, starting with the district magistrates and collectors, chief executive officers, district coordinators, district panchayati raj officers, engineers, etc. This is laudable but needs to be institutionalised so the entire machinery in the district is oriented towards ODF – achievement and sustainability”[10]

Way Forward

Considering the momentum created by the Swachh Bharat Mission, a comprehensive governance approach should be followed that makes it possible to treat problems of access to sanitation in a more effective manner. Actions put in place should be designed to strengthen the capacities of stakeholders, establish participative and more transparent decision-making processes, and reduce tensions between stakeholders, advocacy, and so on. Above all else, ensuring adequate governance means creating a project designed to last and that can be more easily appropriated by its beneficiaries. This calls for setting up programmes to strengthen governance at the local and national levels, help to capitalize on them at the national and international levels, and contribute to international initiatives for knowledge creation, information sharing and advocacy. SBM has made available boundless opportunities for creating a mass impact and we should all, as one take this forward.

References:

[1] Mason, N., Matoso, M., Hueso, A., 2016: Beyond political commitment to sanitation: Navigating incentives for prioritisation and course correction in Ethiopia, India and Indonesia. WaterAid

[2] UNESCO 2016: Concept of Governance: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/strengthening-education-systems/quality-framework/technical-notes/concept-of-governance/

[3] Pandey, K. 2014: Better sanitation key to improving children’s health: World Bank report http://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/better-sanitation-key-to-improving-childrens-health-world-bank-report-43225

[4] Wankhade, K., 2015: Urban sanitation in India: key shifts in the national policy frame. International Institute for Environment and Development Vol 27(2).

[5] SuSanA Homepage: http://www.susana.org/en/about/sustainable-sanitation

[6] Sankar, U. 2016: To be or not to be a toilet: Moving away from a one size fits all approach to sanitation http://wateraidindia.in/blog/not-toilet-moving-away-one-size-fits-approach-sanitation/#comment-98

[7] SuSanA discussion Forum “On the way to clean India” August 2016 http://forum.susana.org/component/kunena/260-theme-1-policy-and-institutions/18530-policy-and-institutions–2-years-of-swacch-bharat-mission-graminrural?limit=12&start=12

[8] Mason, N., Matoso, M., Hueso, A., 2016: Beyond political commitment to sanitation: Navigating incentives for prioritisation and course correction in Ethiopia, India and Indonesia. WaterAid

[9] Sangupta, S. 2016: Usage of toilets in India is over 95 per cent, reveals new NSSO survey 14.04.2016

[10] SuSanA discussion Forum “On the way to clean India” August 2016 http://forum.susana.org/component/kunena/260-theme-1-policy-and-institutions/18530-policy-and-institutions–2-years-of-swacch-bharat-mission-graminrural?limit=12&start=12

Achieving Swachh Bharat: Required change in Mind –set for sustainability by Siddhartha Das (Program Leader, India Sanitation Coalition)

An Introduction

Sanitation in India has got unprecedented political attention and increasing resources have been allocated in the plans and budgets. The Swachh Bharat Mission has given a great opportunity to elected representatives to commit to sanitation and accordingly to enhancing quality of life.

Safe sanitation leads to improved health indicators, potential increase in livelihood options and optimistically, a reduction in poverty. India accounts for 90 per cent of the people in South Asia and 59 per cent of the 1.1 billion people in the world who practise open defecation.[1] Open defecation refers to the practice whereby people go out in fields, bushes, forests, open bodies of water, or other open spaces rather than using the toilet to defecate. The practice is rampant in India and the country is home to the world’s largest population of people who defecate in the open and excrete close to 65,000 tonnes of faeces into the environment each day.

The central government has set aggressive targets for open-defecation free (ODF) communities, and the sector recognises the risk associated with the goal: the target may turn out to be mere construction, often without the desired quality and without adequate hygiene awareness to ensure use of facilities. Despite making significant improvements in ensuring access to improved sanitation facilities (individual and shared toilets) in both rural and urban areas, India has the highest number of people (564 million;) who still defecate in the open.[2] This makes it clear that infrastructure alone cannot tackle the problem.

Compelling Need for Sanitation

Lack of adequate sanitation facilities, results in increased health burdens and environmental costs. Today, one in every two Indians doesn’t have access to safe toilets, harming the health and well-being of Indians, especially children. Only 50 per cent[3] of the total population in India have access to safe sanitation.Lack of toilets is compelling women and girls to defecate in the open which has a direct bearing to their dignity, health and security. It is estimated that every year approximately 186,000 children under 5 years of age die from diarrhoea in India. Improved sanitation can reduce child diarrhoea by 30 percent[4] and increase school attendance among girls.

Better sanitation helps India maintain its polio-free status, reduces the incidence of diseases like cholera and typhoid, and will help make gains toward combating other neglected tropical diseases. Safe sanitation also reduces contamination of water sources. Appropriate systems for collection, conveyance, disposal of solid and liquid waste, and good hygiene practices (such as hand washing, safe use of latrines, menstrual hygiene management, safe handling, and storage of water and food) through appropriate Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) needs to be strengthened.

Sustainability Beyond Construction

Open defecation free (ODF) is more about hygiene behaviour change through continuous sensitisation rather than a mere construction of toilet buildings. A concerted effort by government, WASH champions and other stakeholders is required in achieving this ambitious goal of complete ODF by 2019. The entire sector which includes the government is aware of the importance of behaviour change. Considerable discussions and deliberations have happened in this. However, the level of operationalisation has been limited, something which needs to be urgently addressed.

Also, Solid and Liquid Waste Management (SLWM) is one of the key components of SBM (Rural). Some of the core objectives of SBM is focussing on SLWM in order to achieve overall cleanliness. More than 60% rural households are not connected to clean drainage and only 6% are connected to clean drains. Most of the villages do not have proper facilities on solid waste and waste water management. 88% of total disease burden in rural areas is due to lack of proper facilities for SLWM.[5] To have a holistic solution-oriented perspective, it is important to have an approach that integrates water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

Solutions Through Collaboration

There is a wide spread and commonly held agreement that for the set goals to be more realistic, a robust planning, monitoring, and role clarity together with avoiding duplication is required. The goal set up at the national level needs to be adopted and further strengthened by all the state governments owing to the fact that Rural Sanitation is a state subject. Substantial funds have been allocated by the centre along with flexibility to states to also use funds from other sources.

Resource mobilization plans need to be developed and channeled properly to ensure a proper supply chain. Funds can be generated also in form of Public-Private-Partnership (PPP), loans and donations, MPLADS/MLALADS funds etc. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and PPP would be the prime source of funding to cover up the loose ends. Corporates can assist in covering the GPs for sanitation especially either directly or through CSR. There is needs to sit back reflect and make a collective contribution to the plans and goals that were set in 2014.

One of the biggest challenges the sector is facing is unlocking the CSR funds for sanitation. This in spite of the fact that substantial corporates are willing to invest in sanitation and even more are willing to receive the funds! The biggest reason has been the lack of clarity of utilisation of the funds. Corporates have their own reasons to ensure their branding as a small return of the investments. They also have justifications to invest in projects confined to a restricted geographical location. Important aspect is advocacy so that the government makes it easier for corporates to engage, and guide them by providing the right points of contact within the system, to cut through the red tape especially at the local levels. It’s not just government-corporate.

The 3-way partnership is ideal, bringing in NGOs who understand the ground realities. Along the way, it is key to leverage each other’s strengths and build the capacity of parties like NGOs. The India Sanitation Coalition (ISC) is playing a key role in facilitating those linkages among the different stakeholders. Through its extended membership base, ISC is working closely with the national and state governments for creating a platform for the same. With only two and half years left in the SBM, it is critical that the entire process is fast tracked with visible concrete outcomes.

The SBM is a programme with closely coordinated efforts by corporates, civil society and different ministries. ISC has created a platform in bringing players together to address this. Surely, continuing coordinated efforts will ensure universal access to sanitation in time, and benefit large sections of society which especially includes girls, women and the disabled.

Siddhartha Das is the Program Leader of the India Sanitation Coalition

[1] Source: UNICEF

[2] Source: UNICEF

[3] http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/JMP-Update-report-2015_English.pdf

[4] Source : UNICEF

[5] Source: MDWS workshop report on SLWM).

Key Learnings from a Major Project towards providing Improved Sanitation Facilities through the Construction of 20,000 Household toilets in Barmer district: one of the largest sanitation CSR interventions

Background

The Barmer district has some of the worst socio-economic indicators in India with more than 90 percent people practicing open defacation in rural areas and ~85 percent overall (as opposed to the average of 50 percent in India) as a whole (refer to the table)

Such practices have, in turn, resulted in contamination of nearby water sources, thereby contributing to some of the highest Infant and Maternal Mortality (IMR, MMR) rates in the country.

Barmer Sanitation Statistics

| #. | Present Indicators | Dist. Barmer % | State % | Rural % | Urban % | Source |

| 1 | % Households having toilet facility within premises | 14.9 | 35.0 | 9.7 | 83 | Census 2011 |

| 2 | % Households having Improved toilet facility | 13.2 | 34.1 | 9.4 | 62.8 | Census 2011 |

| 3 | % Households practicing open defecation | 84.7 | 64.3 | 89.8 | 16.8 | Census 2011 |

For example, media reported that in 2013, over 24 cities and towns, including Barmer, Balotra and Jalore, received Government water only once every four days[1]; and Jaipur, the capital city of the state, topped the list of water contamination with as many as 9,628 habitations not having access to clean water. It is estimated that ~75 percent of the Indian villages with multiple water quality problems fall in Rajasthan (Report of Expert Committee on Integrated Development of Water Resources, GoR, June 2005).

In 2013, under the ‘Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan’ (NBA) program, a major sanitation initiative was commenced. We studied several models before finalising our strategy. These included the ‘Maryaada’ model implemented by Hindustan Zinc Ltd (HZL) and that of the Aga Khan Foundation, which has been active in Gujarat and Bihar.

Finally, the model chosen envisaged the Zila Parishad contributing INR 12,000 per toilet and Cairn India, a major corporate active in Barmer, contributed an additional amount of INR 4,000 towards the construction of as many as 20,000 toilets. The beneficiary households would also contribute INR 1000 each to ensure their ownership of the facility constructed. The extra funds contributed by Cairn would go towards ensuring some amount of value-addition, such as:

- Cement bricks used for construction rather than slabs

- A good quality soak pit with cement plaster & covering

- The usage of an iron door with 20” guage Iron sheet

- Water storage tank of 200 litres being provided

- Tiling been done upto a certain level in the bathrooms

- Provision of a washbasin for proper handwashing

The project is being implemented by the RDO Society under the guidance of the Zila Parishad. The parameters on which the agency was evaluated included prior experience in the sector, technical expertise, competency to complete task within project timeframe etc.

The role of the chosen agency was as follows:

- Work with the Gram Panchayat to draw up plans for demand generation and ensure speedy construction as per the required technical specifications

- Provide regular information/reports etc to all stakeholders so that the project could be adequately monitored.

- Designing and Distribution of IEC Materials: to develop IEC materials like, posters, wall paintings, brochure etc which would be circulated amongst school children and community members. The agency also would use the Internationally Awarded Film on Sanitation ‘Let’s Make it Right’ to effectively communicate the message of sanitation across the community.

- Ensure interventions at community level, through ‘triggering’ -a specific tool which has been advocated by many agencies working in the field of sanitation that aims at generating feeling among the target audience towards the “Need of Sanitation”.

- Identify members of and establish a ‘Village WATSAN committee’ that will be responsible for steering the village ODF drive that includes visiting existing areas of open defecation, designing a map of the village and highlighting how open defection is affecting the hygiene condition of the village etc

In another major value addition, the establishment of a Rural Sanitary Mart (RSM) was also faciltated. The chosen agency was asked to set aside a revolving fund which was utilized for aggregating the demands of sanitary items (needed for the construction and maintenance of household toilets). The agency facilitated the establishment of a small unit which can manufacture items like Bricks, pit covers etc.

This was particularly important in Barmer as items such as pipes, doors, paint, cover Slab for the pit etc were not easily available in rural shops and attempting to purchase them individually from the open market increases the cost of these items considerably besides slowing down construction.

Results of first Phase and Change in Strategy

The first phase of the project till mid 2016 saw as many as 7000 toilets being constructed. The utilization was a shade over 40 percent, much higher than in many other parts of the country. Nevertheless, there were a few areas of improvement that were identified:

- Firstly, the project was spread thinly over a number of Gram Panchayats /Villages meaning that while the geographical coverage was noteworthy, measuring and monitoring outcomes was not easy; and nor was it easy to ensure utilization through demand generation activities due to the distances involved (especially as the Barmer district is a very large one-over 28,000 sq kms).

- Attrition rate among local Masons was high

- Inclination towards non contribution by the beneficiary

- Timely release of payments by the Government was an issue

- Implementing agency had not motivation to drive utlisation since payments were linked to construction, not actual usage of the toilets

- Not much interest from the Government, whose representatives did not participate in community meetings. The participation of the sarpanches also was not solicited by the Government; the sarpanches in turn felt pushed

Accordingly, after an internal review in July 2016, while recognizing and commending the constructing of ~7000 toilets by that time, we decided to make a few changes in the strategy. This encompassed the following:

- The selection of Gram Pachayat’s where we would implement the new strategy was to be carefully done. One of the prime considerations was to ensure adequate water availability, as in a water scare area (relevant to the Barmer district, which is part of the Thar desert), the usage of household toilets was likely to be low

- We would focus on fewer Gram Panchayats with an aim to make them Open Defecation Free (ODF). A smaller geographical spread would help us to concentrate our activities towards ensuring maximum usage of constructed toilets as we could undertake more intensive and regular awareness generation drives

- It was also seen that usage of toilets was much higher where an additional bathroom was provided for people to bathe, wash clothes or utensils etc. Hence the focus would be on construction of these twin facilities

- Identification, engagement and use of Motivators would be emphasized on, with regular reviews of achievements

- Sustainability of surveillance Committees is important for ODF hence a dedicated team of people would be used

- Get children to endorse toilet usage and push their parents towards using toilets-through intensive activities in schools etc including exercises/ games on sanitation with their parents

- A database of beneficiaries is being established. They are being contacted through tele-callers who regularly emphasise the need to use toilets and to wash one’s hands.

- In addition to this, a regular SMS campaign is being started towards the same purpose

- We are also planning a ‘toilet beauty Contest’ wherein 1-2 families would get rewarded for the best used and maintained toilet every month.

- In Schools Exercise/Games on Sanitation with Parents will be organized to establish the importance of toilet usage.

- Planting of trees considered sacred in areas of Open defecation.

More importantly, the whole incentive scheme has been changed towards utilizing usage of toilets rather than just construction. This incentive is to be provided to all members in the value chain-the beneficiary so that he uses the toilet in his home, the Gram Panchayat and sarpanches to encourage the community to use toilets and the implementing agency RDO.

Results

The results of the new strategy have been encouraging so far. Outreach activities have been held in several schools; several Panchayat meetings and workshops have taken place with wider participation from various stakeholders. The key points to note are as follows:

- In some cases, beneficiaries have really been keen to get toilets. Besides the contribution of others, they have put in their own funds-sometimes even over INR 30,000 to get toilets in their houses

- Much better support from sarpanches and local leaders

- Many human-centric stories have been noted and have received widespread press coverage in Barmer

- Increased utilization of toilets based on empirical data

- Appreciation from District Administration and faster support in terms of participation

The success of the new strategy has been widely reported and was featured extensively in both the regional and national press, including by the Times of India, the Hindustan Times etc. It is serving as a model for implementation for other corporate and agencies and Case Studies pertaining to this strategy presented across the world at a number of international conferences.

About the Author

Sidharth Balakrishna is Director, Manthan Advisors and heads their Sustainability practice. He led the Sanitation initiative and was responsible for changing the Strategy described in the article above.

He holds an MBA from the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Calcutta and an Economics degree from the Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC), Delhi University and has ~13 years of experience in the energy and infrastructure sectors; and has worked with Cairn India and British Gas in the Strategy function, besides being a Strategy Consultant with Accenture and KPMG. His experience includes advising clients on new country entry strategies, policy and regulatory affairs, Mergers & Acquisitions, growth and diversification etc.

He has also led a number of social development initiatives in the field of renewable energy, Water and Sanitation, Vocational training etc. This includes leading an initiative to establish ~350 safe drinking water units in the Barmer district of Rajasthan, which is perhaps the largest CSR water initiative in the world impacting over a million people, a project that has won several national awards.

He has authored five books and is a Visiting Faculty at a number of management institutes in India including the IIMs. He has presented at a number of international fora in the past on Water and Sanitation, including at London, Myanmar, Muscat, Mexico City, Yangon, Mozambique, New Delhi, Mumbai etc.

He can be contacted at sidharth.balakrishna@gmail.com

[1] http://ibnlive.in.com/news/rajasthan-many-cities-get-water-every-4th-day-due-to-shortage/396982-3-239.html

Havells Honoured with CSR Excellence Award by Rajasthan Government for School Sanitation

Havells, India’s largest electrical products manufacturer, had a yearning to serve the society since long. The Company began its CSR programs well before it became mandatory for certain companies according to criteria led down in The Companies Act, 2013.

Havells’ CSR initiatives are focused on child health, nutrition, education and sanitation. The flagship Mid-day meal program was started in 2005, with 1,500 children every day, and today covers 58,000 children in 688 government schools in Alwar district of Rajasthan, where the Company has five manufacturing plants, including the largest of the 11 that are spread across different states. The company-owned superior infrastructure for preparing and delivering fresh and nutritious meals has a highly automated kitchen spread across a 4-acre plot, deploying 130 cooks and 24 vans with driver and helpers. The Mid-day meal program has led to an increase in the average enrolment number, for both girls and boys, and it was specifically higher for girl students in the target schools.

Understanding a very strong nutrition-sanitation nexus, Havells was desirous of providing sanitation facility in these schools. After evaluating various sanitation technology options, the Company decided to provide the eco-friendly and sustainable bio-toilets that treat waste onsite, in these schools. Havells chose to partner Banka BioLoo, a social enterprise of global acclaim that has bio-toilets at its heart, to install the bio-toilets (or bioloos) in the schools. Representatives of both the companies undertook detailed planning on the structures, layout and the overall designs of the bio-toilet blocks for girls and for boys. Havells provided support, not only from the corporate office but also the local officers in Alwar took keen interest – after all the implementation was taking place there.

The sustainable sanitation initiative strengthened the Prime Minister’s Swachh Bharat Mission through Swachh Bharat – Swachh Vidyalaya. It, also, was another step in the holistic education initiative that Havells is committed to. In the fiscal year 2015-16, Banka BioLoo installed 816 bio-toilets in 102 schools on behalf of Havells, while in 2016-17 another 1,200 bio-toilets would be installed in little over 150 schools. Many research studies have highlighted the importance of adequate WaSH (water, sanitation and hygiene) in increasing school attendance in general, and reducing school dropouts in particular. This is more pertinent for girl students, who have the added dimension of menstruation hygiene. One such study, “The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India” by Water and Sanitation Program, World Bank, concluded that building toilets in schools increases attendance by 11%.

Havells’s school sanitation program is probably one of the biggest in Rajasthan, by any corporate house, that too with a perspective of sustainability and being environmentally-friendly. It, then, wasn’t a great surprise when the Government of Rajasthan, at its first-ever CSR Summit on 7 March 2017 in Jaipur, honoured Havells with the newly-instituted CSR Awards of Excellence in the category of Clean Water and Sanitation. Creating the sanitation infrastructure is not enough by itself, thereby the Company also aims for behavioural change and habit formation to WaSH. Havells has undertaken sensitization programs through interactive sessions with students, teachers, school staff and district education officers. The Company has also published a booklet “WaSH Education in Schools”, which highlights the importance and significance of cleanliness, bio-toilets, clean drinking water and the new three R(s) – reduce, reuse and recycle, helping not only the students but also reaching the families, creating a multiplier effect.

Havells initiatives of inclusive development, more so of supporting education through WaSH-Nutrition in schools, are worth emulating; and Banka BioLoo, the sustainable sanitation implementation partner, is happy to be part of this sanitizing journey.

Sanjay Banka is Managing Director of Banka BioLoo, and a Steering Committee member of Sanitation and Water for All. Banka BioLoo, founded by Namita Banka, in association with the Indian Railways, PSUs, publicly-listed and private companies, Foundations, Non-profit organizations, construction, infrastructure and plantation companies provides bio-toilets in trains, schools, homes, institutes, work sites, and many similar ones in 20 states. Sanjay is considered an expert on sustainable WaSH (water, sanitation and hygiene) and is a regular speaker at international events, including at the UN. He is a prolific writer, and has authored many a piece on sustainable sanitation, nationally and globally. He, strongly, believes in partnerships as a basis for sustainable development. Governments, civil society and businesses should work in harmony for the greater good of the society.

A perspective on sustainable governance and Swacchh Bharat Mission in India -Vandana Nath, India Sanitation Coalition

The sanitation problem in India cannot be understated. While decades of sustained economic growth has made India the seventh-largest economy in the world today, the provision of public services such as water, sanitation, solid waste management, and drainage continue to be a challenge. A lot of programs already have been started in the past decades, however, none of them could fully grasp the full cycle of water management and sanitation. With an urgent need to re-energise and remodel its approach, the Government of India launched the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) in 2014. Also the 2015 Sustainable Development Goal 6 “represents a significant deepening of ambition, aiming to ‘achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation’ by 2030”[1]. Today, India has a historic opportunity to address the problem of sanitation in its entirety using the momentum generated by SBM to realise the ambition of sustainable sanitation, one of the prime goals of SDGs.

The inauguration of SBM with focus both on rural and urban areas is an achievement. SBM brought sanitation and water “on the table”. The message is clear and with the new SDGs awareness has increased massively both nationally and in the international sphere. Increasingly projects and NGO are settling for improving sanitation. Campaigns and events like Global Citizen point citizens to realize the urge for a Swachh Bharat. GOI creates different-different policies in and around the WASH umbrella, not only toilet building activities but sees the need for integration of sectors like menstrual hygiene management (MHM Guidelines), corporate social responsibility (Swachh Kosh) or WASH in school activities (Swachh Vidyalaya).

Though there is no shortage of policy level recommendations at the central level, their impact and infiltration at the ground level is very limited. To create sustainability, these policies need to work hand-in-hand with the implementation of its programs. There is a dire need for thought leadership to move this forward. Policy advocacy is not merely the creation of laws and regulations; it has to create an enabling environment for sustainable change. Sanitation also needs good governance. UNESCO understands Governance as an act

“… to refer to structures and processes that are designed to ensure accountability, transparency, responsiveness, rule of law, stability, equity and inclusiveness, empowerment, and broad-based participation. Governance also represents the norms, values and rules of the game through which public affairs are managed in a manner that is transparent, participatory, inclusive and responsive. Governance therefore can be subtle and may not be easily observable. In a broad sense, governance is about the culture and institutional environment in which citizens and stakeholders interact among themselves and participate in public affairs. It is more than the organs of the government.”[2]

This is a huge challenge for India at this time. Though the central government has taken the bold initiative in its SBM, there is much work needed to translate these policies into real solutions and engage not only national, but also state and local bodies as well as the society as a whole.

The need is to trickle these solutions to the last mile with an efficient governance and effective implementation. The right governance system and a model to help address “Produce to Use” strategy are important. This process is indeed not an easy one, but efforts and motivation are the first step towards achieving a “Swachh Bharat”. However, a “one size fits all” didn´t, does and will not work in the Indian context. To tackle the problem of the last mile, a closer look in the Governance body and process has to be taken forward. Different important challenges that SBM urgently needs to work on are explained here.

Integration of the full water and sanitation cycle

The image of sanitation has to move beyond “going to the toilet”. Since SBM started in 2014, the main focus from governance has been construction of toilets. With the current mission India runs the risk of neglecting the whole wastewater cycle. Sanitation is a complex and intertwined topic. It has significant impact on health, nutrition, security, environment and human rights. According to the World Bank 47% of children could be saved from diarrhoea if sanitation systems would be offered broadly.[3]

Understanding sanitation often does not include the big picture of sanitation. Once a toilet is constructed, is has to been maintained, the disposal of human waste has to be safely managed and people actually have to use the toilet regularly. On top of that, sanitation also includes the knowledge of hygiene such as handwashing activities and menstrual hygiene actions. The SBM lacks the governing of the solid and liquid wastewater management. Sewage systems, on-site systems like septic tanks and other solutions are not prioritized by GOI. The conjunction from sanitation to drinking water is not applicable. On-site systems also need to be operated and emptied. The next step has to be a safe disposal in a treatment plant or sewerage system. SBM has set numbered goals in toilet construction and ODF, which are handy to monitor. But it lacks the full understanding and implementation of policies that focus on the full cycle. “This implies paying attention not only to wastewater conveyance and treatment, but also to less visible concerns like poor construction of on-site systems and lack of operations and maintenance”[4]. The Shit Flow Diagram (SFD) tool is a good visualization for explaining the whole cycle. For example in Tirupati, 30%[5] of the wastewater is untreated. In Delhi the number is even as high as 46% SBM is prone to toilet construction without taking these points into consideration. In Nashik, only 15% are not managed safely.[6]

This leads to the question of how sustainable the current governance/policy of SBM actually is.

Sustainable Governance and long term vision

SBM with the deadline of 2019 tries to become ODF. But what comes after that deadline? What if all the toilets constructed now will not be in use any more? The need for sustainable solutions should be taken seriously, not only on the environmental perspective but also for economic reasons and financing of sanitation project. According to the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA), and the members of the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council as the “Bellagio Principles for Sustainable Sanitation” during its 5th Global Forum in November 2000: Human dignity, quality of life and environmental security at household level should be at the centre of any sanitation approach.

- In line with good governance principles, decision making should involve participation of all stakeholders, especially the consumers and providers of services.

- Waste should be considered a resource, and its management should be holistic and form part of integrated water resources, nutrient flow and waste management processes.

- The domain in which environmental sanitation problems are resolved should be kept to the minimum practicable size (household, neighborhood, community, town, district, catchments, city)[7]

Sustainability in sanitation the following points should be implemented for sustainable sanitation: Waste should be considered a resource, and its management should be holistic and form part of integrated water resources, nutrient flow and waste management processes. The sustainability aspect is missing on paper and in the heads of people. A longterm vision on sanitation and drinking water after 2019 should already be published by now. Policies currently lack this aspect.

Capacity building and effective governance

The capacity and resources for sanitation are limited. Especially in urban areas, regulations need to be implemented for proper waste disposal. A “one size fits all” approach is not working.[8] Communication between local bodies and higher institutions is missing. Local communities are often not given the chance to communicate their needs into the political level. Effective governance means to create rules and norms which fit local realities. This means also a democratic, inclusive approach, where politicians not only act according to some policy plan which has to be fulfilled, but also listen to the beneficiaries of a policy. The responsibility for drinking water and sanitation lies at the government site. Governance in a federal state tends to get slow and confusing. A lot of policies are being implemented from different actors. The legislative framework shifts the major responsibility of sanitation and wastewater management to state and/or local bodies. In reality, national agendas on sanitation influence the various state sanitation agendas. Especially financial support mainly comes from national ministries. On the national level, the Ministry for Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) mainly leads the SBM for rural areas, whereas the Ministry for Urban Development (MoUD) established an urban SBM. WASH activities like Swachh Vidyalaya are coordinated by the Ministry of Human Resource Development. If it comes to sanitation systems and local infrastructure within households, the Ministry for Housing and Urban Poverty Allevation (HUPA) takes the lead. The capacity for sanitation issues in government bodies has been implemented, but effectiveness in communication and actually achieving goals still is missing. A clear framework for actions has not been published so far. That gives the feeling of rather impulsive actions in WASH that lack management of implementation actions, especially in local areas.

Another fact that has to be pointed out is that capacity of public service involvement in sanitation sector is very low. Most septic tank cleaners operate privately. Standards of waste disposal do not reach yet an implementation level. The Delhi Shit Flow Diagram shows that although toilet coverage is high, only 56% of the human waste “produced” is being disposed safely.[9] Capacity building for understanding of the whole cycle is missing and often hidden by non-transparent government responsibilities. At the moment, the “trend” in the sanitation sector is FSM, which is very much needed in a lot of places around India, but leaves out the opportunities of other technologies and off-site sewerage systems, that are hardly seen in any big cities. The window of opportunity for sanitation systems in India is there, it just needs to be filled properly and timely.

On the other hand Corporate Social Responsibility is on the rise in India. Companies have started working on sanitation through their corporate social responsibility (CSR) wings and private foundations. These are early days and except for a few, large-scale action has been limited.

Ownership and Collaboration

Everybody does it but less people care for it. Sanitation systems tend to create the impression that you can flush and give away human waste. “Your own business” no longer is your own business when it comes to sanitation. It needs the individual to understand the scope of WASH impacts every single person has. Creating policies on national level is simply not enough to reach Swachh Bharat. “Given the scale of the challenge and India’s very disparate socio-political landscape, performance varies from State to State and even within a State. Too often we depend on an individual without making the change systemic”, Naina Lal Kidwai stated in an online discussion.[10]

Governance has to move beyond creating rules and policies towards integrating a nations citizen. That requires a sense of responsibility and taking on ownership for their own good. “The positive incentives identified for prioritisation of sanitation are necessary, but not

sufficient. Peoples’ perceptions about autonomy and authority shape how they respond to incentives to prioritise sanitation”.[11] Activities on behaviour change are therefore very much needed. In the biggest democracy in the world, the people of India has to understand and more importantly want the need for Swachh Bharat. GOI cannot do the job on its own, as state level actors cannot provide sanitation services. As a collaborate action between citizens, institutions, organisations and government bodies, everybody has to work together more instead of scape-goating a certain policy or one single institution. Sanitation and access to clean water is something everybody should have and every person should want. However, Swachh Bharat will not appear magically, but through hard work, new ideas, creating solutions by collaboration.

In the first year of SBM, more than 5.8 million toilets were constructed in rural areas and about 1 million in urban spaces.[12] How many of them are in use? Are they maintained well? Is the waste disposed safely? Who disposed waste? All these and many more questions come up. SBM is not only a mission about achieving numbers. Governance stops at the construction of toilet so far. The problem is that people expect GOI or state governments to subsidize toilet constructions, conduct workshops or set up septic tanks, but they do not plan to engage themselves. Sanitation at this level is not simply a public service. It’s a goal everybody has to work on. “The successes we are seeing now are largely due to the leadership and commitment of district officials, starting with the district magistrates and collectors, chief executive officers, district coordinators, district panchayati raj officers, engineers, etc. This is laudable but needs to be institutionalised so the entire machinery in the district is oriented towards ODF – achievement and sustainability”[13]

[1] Mason, N., Matoso, M., Hueso, A., 2016: Beyond political commitment to sanitation: Navigating incentives for prioritisation and course correction in Ethiopia, India and Indonesia. WaterAid

[2] UNESCO 2016: Concept of Governance“ http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/strengthening-education-systems/quality-framework/technical-notes/concept-of-governance/

[3] Pandey, K. 2014: Better sanitation key to improving children’s health: World Bank report

[4] Wankhade, K., 2015: Urban sanitation in India: key shifts in the national policy frame. International Institute for Environment and Development Vol 27(2).

[5] Roeder, L. (2016). SFD Report (draft) – Tirupati, India – SFD Promotion Initiative. Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) http://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/3-2570-7-1464694097.pdf

[6] Roeder, L. (2015). SFD Report – Nashik, India – SFD Promotion Initiative. Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) http://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/3-2372-7-1457445850.pdf

[7] SuSanA Homepage: http://www.susana.org/en/about/sustainable-sanitation

[8] Sankar, U. 2016: To be or not to be a toilet: Moving away from a one size fits all approach to sanitation http://wateraidindia.in/blog/not-toilet-moving-away-one-size-fits-approach-sanitation/#comment-98

[9] Down to Earth 2016: Urban Shit http://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/urban-shit-53422

[10] SuSanA discussion Forum “On the way to clean India” August 2016 http://forum.susana.org/component/kunena/260-theme-1-policy-and-institutions/18530-policy-and-institutions–2-years-of-swacch-bharat-mission-graminrural?limit=12&start=12

[11] Mason, N., Matoso, M., Hueso, A., 2016: Beyond political commitment to sanitation: Navigating incentives for prioritisation and course correction in Ethiopia, India and Indonesia. WaterAid

[12] Sangupta, S. 2016: Usage of toilets in India is over 95 per cent, reveals new NSSO survey 14.04.2016

[13] SuSanA discussion Forum “On the way to clean India” August 2016 http://forum.susana.org/component/kunena/260-theme-1-policy-and-institutions/18530-policy-and-institutions–2-years-of-swacch-bharat-mission-graminrural?limit=12&start=12

Towards Sustainable Sanitation Systems

The old man was well ahead of his time in more ways than one! He had installed dry sanitation systems in his hermitage. He was an advocate of sanitation systems that do not use copious quantities of water to transport pee and poo. None of the old man’s disciples who formed government truly understood his maverick ideas…be it on sanitation or on education! Anyway, we will speak on the old man’s ideas on education elsewhere. Regarding sanitation, let us read one of the pieces that the old man wrote on 13th September 1925, which appeared under the title ‘Our Dirty Ways’ in Navajivan

- Both excretory functions should be performed only at fixed places.

- To pass urine anywhere in a street, at any place not meant for the purpose should be regarded an offence.

- After passing urine at any selected place, one should cover up the spot well with dry earth.

- Lavatories should be kept very clean. Even the part through which the water flows should be kept clean. Our lavatories bring our civilization into discredit; they violate the rules of hygiene.

- All the night-soil should be removed to fields.

“. . . If my suggestion is followed, no one would need to remove night-soil, the air would not become polluted and villages would remain very clean.”

Cut to 1947!

Probably the most damaging non-indigenous concept that we adopted unthinkingly is one of water-based sanitation systems. Both versions of “drop and store” and “flush and forget” sanitation systems have caused irreparable damage. Improper disposal of feces and wastewater has led to pollution of our waterbodies. Pathogens from the waste pollute our water and food and eventually pollute our own bodies. When 80% of the diseases in India are a result of improper sanitation, much more than one’s own health is affected. Specifically, 73 million working days are lost annually due to sicknesses caused by unsafe water and lack of sanitation. The economy of India as a whole is impacted since people must pay for visits to the health centre and on occasion lose their jobs because of an inability to go to work.

So, is there a magic wand? The old man, we all know we are talking about MKG, would have wanted each one of us to use the magic wand! Had he lived few more years, the next contest he would have announced would have been on a toilet system. But of course, for the old man liberty meant universal responsibility!

If you are a bit tired by now and are looking for some semblance of a technology solution, the good news is many attempts have been made and continue to be made to develop sustainable sanitation systems. The main objective of a sustainable sanitation system would be to protect and promote human health by providing a clean environment and breaking the cycle of disease. In order to be sustainable, a sanitation system has to not only be economically viable, socially acceptable, technically and institutionally appropriate, it should also protect the environment and conserve natural resources.

Here are some sustainability criteria:

- Health and Hygiene:includes the risk of exposure to pathogens and hazardous substances that could affect public health at all points of the sanitation system from the toilet via the collection and treatment system to the point of reuse or disposal and downstream populations. This topic also covers aspects such as hygiene, nutrition and improvement of livelihood achieved by the application of a certain sanitation system, as well as downstream effects.

- Environment and Natural Resources:involves the required energy, water and other natural resources for construction, operation and maintenance of the system, as well as the potential emissions to the environment resulting from its use. It also includes the degree of recycling and reuse practiced and the effects of these (e.g. reusing wastewater; returning nutrients and organic material to agriculture), and the protection of other non-renewable resources, e.g. through the production of renewable energies (such as biogas).

- Technology and Operation:incorporates the functionality and the ease with which the entire system including the collection, transport, treatment and reuse and/or final disposal can be constructed, operated and monitored by the local community and/or the technical teams of the local utilities. Furthermore, the robustness of the system, its vulnerability towards power cuts, water shortages, floods, earthquakes etc. and the flexibility and adaptability of its technical elements to the existing infrastructure and to demographic and socio-economic developments are important aspects.

- Financial and Economic Issues:relate to the capacity of households and communities to pay for sanitation, including the construction, operation, maintenance and necessary reinvestments in the system. Besides the evaluation of these direct costs, the external costs and indirect benefits from recycled products (soil conditioner, fertiliser, energy and reclaimed water) have to be taken into account. External costs include environmental pollution and health hazards, while benefits include increased agricultural productivity and subsistence economy, employment creation, improved health and reduced environmental risks.

- Socio-cultural and institutional aspects:the criteria in this category refer to the socio-cultural acceptance and appropriateness of the system, convenience, system perceptions, gender issues and impacts on human dignity, the contribution to food security, compliance with the legal framework and stable and efficient institutional settings.

The old man would have concurred with these principles. Ok! So, what kind of products at household level and systems at city level come about by using these principles? Well, let us begin with products. In different contexts, the products would be different.

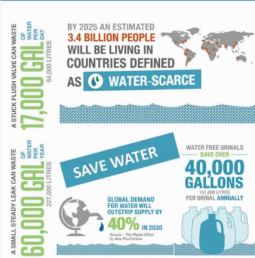

In the urban institutional context, one product from the sustainable sanitation movement is the “waterless urinal”. The waterless urinal is a product which saves between 40,000 to 75,000 litres of freshwater per urinal seat per year. In this context, IIT Delhi has taken a lead and converted about 100 urinals in the academic complex to waterless urinals. The conversion of existing urinals to waterless urinals has been carried out by Ekam Eco Solutions – an IIT Delhi based startup company. To know more about Ekam Eco Solutions, look up www.ekamecosolutions.com

In the rural household context, there is the “urine diversion dry toilet” which opens up the possibility of treating pee and poo as resources! The yellow line output “pee” could be used as liquid fertilizer – rich as it is in nitrogen and phosphorous and the brown line output “poo” gets composted – so as to ensure pathogen destruction before being used as soil conditioner.

- Globally, India has the largest number of people, more than 620 million still defecating in the open. About half the population of India use toilets.

- India, at the current rate of progress will only achieve the sanitation target of MDG 7–c in 2054.

Applying sustainable sanitation at city scale, one begins to study nutrient cycles – Phosphorous and Nitrogen recycling. City scale sustainability requires adoption of closed loop approaches – in which the phosphorous and nitrogen which came from the farm and fish, through the food into our bodies, return to those very ecosystems. A global research coordination network by name Phosphorous RCN is researching into global P cycle to better understand P sustainability by recycling Phosphorous effectively and also by enhancing its use efficiency.

What can you do to promote sustainable sanitation? You can join UNICEF’s digitally led campaign to campaign for open defecation free India “Take Poo to the Loo”. But why this campaign? Because, daily 620 million Indians are defecating in the open. That’s half the population dumping over 65 million kilos of poo out there every day. If this poo continues to be let loose on us, there will be no escaping the stench of life threatening infections, diseases and epidemics. Log on to the website www.poo2loo.com and take a pledge to campaign for eliminating open defecation.

Also, if you want to know more about where sustainable sanitation has been successful all over the world, visit www.ecosanres.org or www.susana.org.

If you would like to promote sustainable sanitation by installing product in your office or home, visit the webpage of IITD startup company www.ekamecosolutions.com or call CEO Uttam Banerjee on +91 9999807207.

– Dr Vijayaraghavan M Chariar is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Rural Development and Technology, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. He is a joint Faculty at IIT Delhi’s National Resource Centre for Value Education in Engineering where he delivers courses and workshops on “Wisdom-based Leadership” for professionals and institutions. Dr Chariar’s research interests are Design for Sustainability, Traditional Knowledge Systems, Ecological Sanitation and Wisdom-based Leadership. He has been a mentor to several youth who have taken the path of social entrepreneurship. Dr Chariar serves as Chairman of the sanitation startup Ekam Eco Solutions. He was awarded the Fulbright Visiting Professorship 2012-13 as part of which he affiliated with the College of Technology and Innovation, Arizona State University, Mesa, Arizona. Dr Chariar is a sought after speaker on entrepreneurship, innovation and sustainability. He has several publications and patents to his credit.

Unlocking Priority Sector Lending for Sanitation

Priority Sector Lending is an important role given by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to Scheduled Commercial Banks and Foreign banks in India to ensure assistance from the banking system to those sectors of the economy which has not received adequate support of institutional finance. Along with other amendments to the Priority Sector Lending (PSL) guidelines lending for sanitation was made a part of PSL on 23.04.2015 as a part of Social Infrastructure, and this included bank loans up to a limit of ₹5 crore per borrower for building social infrastructure for activities namely schools, health care facilities, drinking water facilities and sanitation facilities in Tier II to Tier VI centres.While it is very welcome there are some challenges to fulfilling this spending criterion.

- Lack of awareness amongst the banks, financial institutions, intermediaries and the beneficiaries on the inclusion of sanitation in PSL, and the various avenues to access and utilize these funds.

- Lending small ticket loans for toilet construction can be a costly exercise for banks, and this creates a demand for alternative delivery mechanisms such as Micro-Finance Institutions (MFIs) and Self-Help Group (SHG) Federations. In India, there are over 54 million clients attached through various SHG federations and more than 6 million clients with MFIs.

This being said, MFIs often perceive sanitation loans as consumption spending, and not income enhancing, and accordingly assign higher risks to these loans. This makes them wary of lending. There is a tremendous need to change this thought through capacity-building of MFIs to show the proven impact of sanitation on improved earnings - Community mobilization needed to create preparedness for taking loans.

- Last mile connectivity in receiving funds in a timely manner, and in accessing supplies and resource people to build the toilets.

- Create links between district, block, and GP level governments, for smoother release of incentives/subsidies

- Work with technology providers in direct bank transfers, payment banks where money can be pulled out and directed to the intermediate, and repayment of money going from government to MFI. As costs reduce, possibly interest rates on these loans for the beneficiaries could lessen.

- Attract more MFIs to sanitation through capacity building of the opportunities

- Support turnkey solutions: help in the procurement of materials, mobilization campaigns, release of subsidy, government alignment, source/build capacity of contractors and masons, and standardized toilet design and cost.

WATER BODIES – POOR MAN’S SANITATION SINKS?

Are Waterbodies the poor man’s sewage sinks? And are the city’s poor doomed to live in areas prone to chronic sanitation, drainage and water logging problems?

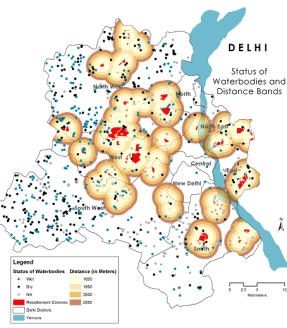

The results of a GIS mapping based study done by FORCE[1] and funded by GIZ[2] as a part of its ICPP program, certainly seems to say so. This study was done to explore the linkages between water bodies in Delhi and resettlement colonies.

In terms of the status of sanitation in resettlement colonies, the study echoed the observations often voiced by Non-profits – that those are not substantially better than the conditions in unauthorized slums. The alarming fact revealed by the study is that prima facie, it seems that the poor sanitation condition has a far more basic genesis than was earlier assumed.

So far, social workers have assumed that the poor sanitation conditions are only because of a lack of co-ordination between the multiple authorities involved in rehabilitation of the poor. Delhi has a unique problem in this respect owing to the duality in its governance by both the central and state governments. Our detailed case studies verified this fact but also revealed another shocking fact.

Our detailed case studies revealed that it took a minimum of 10 years and upto 26 years from the time of construction to bring sewer lines into a resettlement colony! Organized garbage disposal systems seemed to be last on the priority list of the planners since it is not present even after 26 years in some areas. This means that for atleast 10 years, the residents of a resettlement colony live without any access to sewage and garbage disposal systems.

The resultant unscientific, unplanned and unhygienic coping up methods followed by residents are largely responsible for the horrible state of sanitation in these areas.

The most critical revelation of our study was, however, was that the Resettlement colonies were doomed to be plagued by sanitation problems from the day they were conceptualized. The reason is that there seems to be a clear tendency of Resettlements to be located within the core catchment of one or more water bodies.

In 90% cases, water bodies[3] are located either within the boundaries of the resettlements or within a 1.5 km buffer zone. Thus, the land selected for the resettlements was topographically placed in a depressed zone. As a result there was an inherent tendency of the area to be waterlogged – an observation that was verified by the interviews conducted with residents of those areas. More importantly, the negative slope would make it difficult or very expensive to link the area’s internal sewerage and drainage with the peripheral trunk lines.

In 90% cases, water bodies[3] are located either within the boundaries of the resettlements or within a 1.5 km buffer zone. Thus, the land selected for the resettlements was topographically placed in a depressed zone. As a result there was an inherent tendency of the area to be waterlogged – an observation that was verified by the interviews conducted with residents of those areas. More importantly, the negative slope would make it difficult or very expensive to link the area’s internal sewerage and drainage with the peripheral trunk lines.

The fact that after 1990, there seems to be a clear trend towards locating the resettlements in the northern peripheral wards of Delhi, further writes the obituary of sanitation. Being the outermost, least developed parts of Delhi, there are no sewer trunk lines or garbage disposal points in the vicinity of any of the new resettlements. Hence, even if internal sewer lines are laid, there is no planned outfall for the sewage. The high water table in these areas makes the situation worse, as it not only makes sewage disposal difficult but also makes the groundwater more susceptible to contamination due to sewage seeping from internal drains and water bodies.

Thus the study unfolded a dual tragedy – the institutionalization of the neglect of Water Bodies and the neglect of the poor. It has shown a deliberate act of the government in choosing to make resettlement colonies within the core catchments of water bodies. Not only is this disastrous in terms of sanitation provisions for the resettlements, it sounds the death knell for water bodies too.

The key conclusion that emerges from this study is that, water bodies are playing the role of sanitation waste sinks even for planned resettlement colonies. In view of this and the fact that the choice of location makes the resettlements vulnerable to failure of sanitation systems, the policies governing Resettlement Planning need to be re-examined.

(Excerpt from a working paper on Delhi’s Water Bodies and Sanitation[4])

For more information on the topic or for discussion, you are welcome to email to jyoti@force.org.in

– Jyoti Sharma, President FORCE and PJRM FORCE Trust. Also Taubman Fellow & SEIR at Brown University, USA

———————————————————————————————————–

- [1] Forum for Organized Resource Conservation and Enhancement (FORCE) www.force.org.in

- [2] https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/368.html

- [3] Detailed GIS map of Water Bodies in Delhi – http://force.org.in/achievements/policy-research-innovations/water-bodies-delhi/

- [4] Paper Authors: Jyoti Sharma (FORCE), Aparna Das(GIZ) and Shubham Mishr(GIS Consultant)

Re- Engineering Sanitation in India

It feels wonderful to be a sanitation practitioner and expert, living in a time and in a country where sanitation is almost on the verge of becoming a national obsession in both policy talks and programme implementation. This has been triggered by the launching of Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) from the ramparts of Red Fort by Honourable Prime Minister of India Sri Narendra Modi.

SBM, the newest version in the not so long history of sanitation programmes in India, encompassed urban areas in its mission, increased the sanitation financing and linked open defecation free concepts on behaviour change with an unprecedented construction drive of individual household sanitation facilities across the country.

However, in spite of this much needed and renewed obsession with sanitation, there is hardly any paradigm shift or conscious efforts to re- engineer the sanitation programme in rural and urban India against the backdrop of our centuries old track record of dodging the issue. My thought on the main pillars of this process of re- engineering sanitation in India are based in breaking some key myths related to the sanitation programme in India. These are outlined below.

Myth # 1 – the cost of a sustainable household Toilet is Rs. 12000 as per incentive offered under SBM (Rural)

Perhaps this is the biggest myth among implementing organizations for both states and people. SBM offers an incentive for household toilet construction not a subsidy-. The results of this myth have been devastating to the sanitation sector. Consider this. Many implementing organizations in states and therefore people in rural areas have this notion that they have to construct a toilet in 12000 odd rupees received by government – means they trust that Rs. 12000 is the cost of a sustainable toilet in their household across a diverse and vast country like India.

Even a novice civil engineer will tell you that the cost of a sustainable household toilet will vary from place to place and will require some greater co-financing by the household as per their aspiration level, choice of material for construction and technology (e.g. Septic tank, twin pits, bio toilets etc.) and add on features such as storage tank, hand washing facilities etc. Therefore, it is important to take the message to the implementers of SBM and people that adherence to technical design and drawings of different kinds of sanitation systems for toilet construction and co- financing is key to sustainable sanitation, no matter what it costs. Based on their affordability and preferences, the household can choose a toilet design based on available on-site or off- site technologies in the area.

Year after year , there is increasing demands from state governments to the central government to increase the subsidy ( oops .. incentive) from Rs.12000 to up to Rs.25000 based on the understanding of state governments of what it costs to construct an household toilet ( latrine cum bathroom with hand washing facilities ). Obviously, state government’s want 100% of the cost of Individual household toilets to be subsidized. But there is a catch here. Catch number 1 is that the sense of ownership of a toilet which is completely constructed using government’s incentive is less therefore it is more unlikely to be used by all family members. Catch number 2 is the Community led Total Sanitation Approaches (CLTS) which triggers people’s action to become opendefecation free communities and has been widely used by developmental agencies in India for promotion of SBM. Prompting complete financial dependency for the construction of household toilets on government agencies (100% subsidy for cost of toilet approach) dismantles the very basic premise of CLTS- that people and communities can take charge to go for open defecation free using appropriate sanitation options ensuring sustained behaviour change based on community pressure. As a result, what we see of CLTS in India is a tool for Information, Education and Communication (IEC) rather than a tool for triggering community action in many cases.

Myth # 2 – The cost of sustainable sanitation is high and therefore this is a low priority among rural and urban poor.

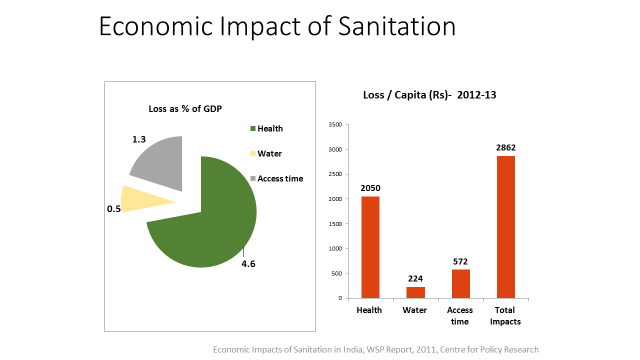

Nothing can be as far from the truth as this notion. But this premise suits everyone and therefore it prevails as a deep rooted myth. So much so that even the poor have started believing in the status quo on sanitation. However, the good news is that it makes sense to invest in a sustainable household toilet by rural and urban poor. Consider economic benefits from sustainable household sanitation. If you explain to an ordinary citizen thatIndia loses 6% of its GDP due to lack of adequate sanitation, the likeliness that this resonates with them is bleak except for being informed of some interestingeconomic data. However when you explain toa family of 5 persons that by not having a household toilet,their family is losing out annually an amount of Rs. 10250 /- approximately on health expenditurewhich could be easily saved, There is a high chance that that you get an affirmative nod, listening ears and engaging minds.

Figure-1: Loss due to inadequate sanitation

Most of the estimates say that a sustainable and aspirational individual household toilet (a latrine cum bathroom with handwashing facility) is achievable within Rs.15000 to Rs.30000 per unit (connection to sewerage /Twin Pit/ Septic Tank with seepage pit /Bio Tanks with Seepage pits). However, the incentive to the eligible beneficiaries under SBM urban remains limited to Rs. 12000/ per household in rural areas and Rs. 8000 to Rs. 13000 per household in urban areas in many states.

The argument that needs to be taken to the people is that it makes perfect economic sense to invest in a sustainable and aspirational toilet even if they have to co- finance the cost by an additional amount required to construct a sustainable and aspirational toilet, as the benefit cost ratio (estimated to be 7.7 in case of SE Asia as per one of the studies) of construction of sustainable and improved toilet is too high to ignore. With MFIs getting increasingly involved for soft loans for sanitation financing by household and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds being increasingly committed to support SBM, the time could not have been better to break this myth. In turn, to help people with getting access to their aspirational and sustainable toilet and access to sanitation financing. This indeed will ensure to plug the leakages between toilet construction and its usages and also increase the life of a toilet to live its full design year at least, if not more.

Myth # 3 – Of technological puzzles , perceptions and realities

There are a number of myths associated with sanitation technologies being implemented under SBM (Rural) and SBM (urban). How often do we hear that on-site is better than off -site sanitation solutions in the Indian context? You may also hear of the poor quality of Septic Tanks being constructed and therefore surrounding pollution. How often do we attribute governance/management/planning failures to technological failures, for example the. performance of Sewerage Networks and Sewerage Treatment Plants.

The point here is that the implementation of SBM will need all the technologies that are available and probably many more for sustainable sanitation solutions which are context specific, affordable and require minimum operation and maintenance interventions or costs. However, there are no silver bullets here because each of the technology needs to be managed. These myths related to technological puzzles, perception and scientific realities can be overcome by bringing in this knowledge and expertise within the domain of each household in a language which can be best understood by them. The best suited for the role of scientific communicators can be school and college children and therefore it is important to make this simplified technological knowledge on sanitation as part of curriculum and discussions in the schools and colleges of India.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here at those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion, standpoint or policy of the organization and networks that he works for and works with.